Representation learning studies how we can train models to learn a semantically-meaningful representation embedding of the input data. That is, given some inputs (most commonly images), we want to “compress” it into some form that preserves its meaning. Representations learned in this manner can then be adapted for any task by predicting the desired target using these representations rather than directly from the input.

Representations are generally learned via self-supervised learning, either with “pretext” tasks or contrastive objectives.

Pretext Tasks

Many self-supervised methods train a model in a supervised manner by augmenting the unlabeled dataset to artificially create pretext tasks. Some examples are as follows:

- For each image, form distorted variants via translation, rotation, scaling, or color shifts and learn to classify the distorted variants to their original.

- Rotate images randomly and learn to rotate them back to the original.

- Crop two patches from an image and learn to associate their relative spatial relationships. Similarly, we can also divide the image into patches, randomize their order, and learn to un-shuffle them back to their canonical positions.

- Recover the original image from a grayscale variant (known as colorization).

Other more advanced techniques take inspiration from 🎨 Generative Modeling to learn a model that can generate parts of the input image:

- Denoising autoencoder: given an image corrupted by noise, recover the original.

- Context encoder: given an image with a missing patch, recover the original.

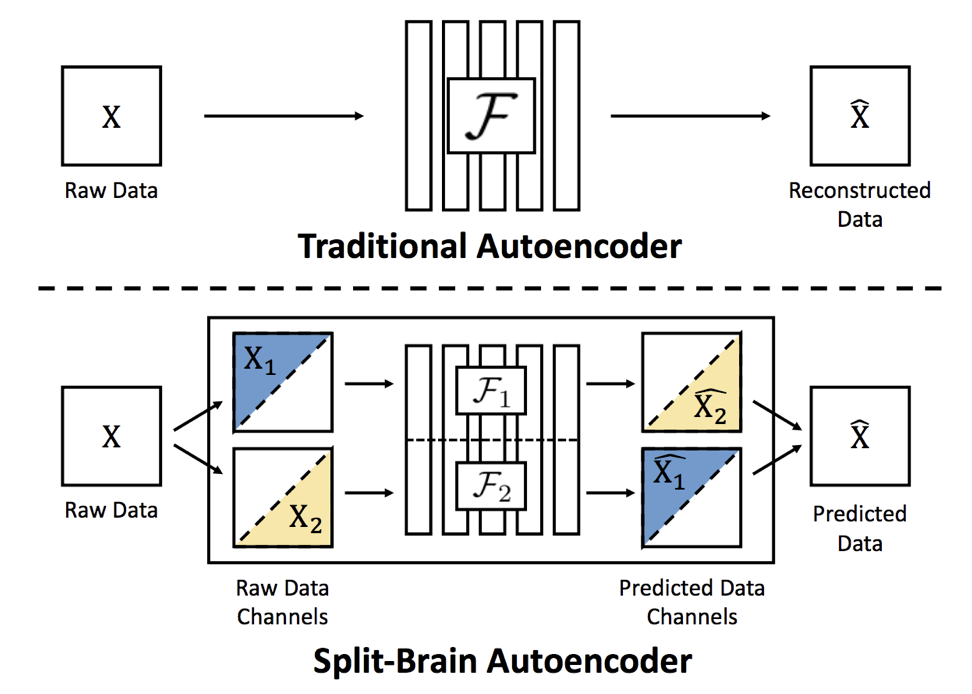

- Split-brain autoencoder (pictured below): predict complementary missing color channels using two sub-networks.

If we have video data, we can take advantage of the temporal relationships between frames for more powerful self-supervised tasks. Many of these tasks resemble contrastive objectives below.

- Given patches of the same object at different times and a random third patch, learn an embedding that makes the similar patches closer than with the third.

- Determine which sequence of frames is in the correct or incorrect temporal order.

- Predict a video’s arrow of time (whether it’s playing forward or backward).

- Colorize videos by tracking pixels across frames (via embedding similarity) and coloring a new frame with tracked pixels from the former frame.

Contrastive Objectives

Rather than learning some pretext task, which might cause our features to be specialized toward that task, we can learn some general embedding space with a notion of “similarity” between samples. Contrastive objectives learn this space by attracting similar samples and repelling different ones.

- Contrastive loss: the standard contrastive loss seeks to minimize distances between samples with the same label and maximizes distances between those with different labels:

For dissimilar pairs, we define hyperparameter

- Lifted structured loss: we can check all possible pairs in a batch; for positive pairs

and negative pairs and distance :

In practice, the nested max operations can be relaxed to a soft maximum for smoother optimization,

![[20230406130932.png#invert|300]]

4. Multi-class

Note that the inner product is essentially the inverse of a distance norm; the more similar the two embeddings are, the larger their inner product.

5. ℹ️ InfoNCE: framing contrastive learning in the context of maximizing mutual information between similar samples, we can derive the InfoNCE loss over a set