A remote procedure call (RPC) is an abstraction that allows a client to call a function that executes remotely on a server. The user-side looks similar to a normal function call, and RPC handles the messaging details under the hood—no need to pack and unpack messages, etc. In other words, RPCs are transparent, looking the same whether the server is local or remote (location transparency) and working regardless of the server architecture, endianness, or programming language (access transparency).

In a local function call, the steps are as follows:

- Caller pushes arguments on stack, jumps to function.

- Function runs.

- Function loads return value into register or stack, function returns.

There are three ways to pass parameters:

- Call-by-value: caller copies parameter value to callee, callee’s changes don’t affect caller. Looks like

void foo(int a). - Call-by-reference: caller passes a pointer of variable to callee, callee’s changes do affect caller. Looks like

void foo(int *a). - Call-by-copy/restore: similar to call-by-value, but we copy the value back to the caller after the function returns. This is less commonly used.

Stubs

To copy the parameters, the client and server have special function stubs:

- Client stub takes parameters, puts them into message (marshaling), and sends the message over the network, waits for response.

- Server stub extracts parameters from the message (un-marshaling), calls the function, and sends the return value back.

The server likely has multiple functions available, so to identify them in the message, the functions are grouped into interfaces and assigned a unique identifier. To receive messages from clients, the server runs a central loop that uses the function and interface ID to decide which stub to call.

Generation

Writing stub code is tedious and error-prone, and we can actually build a stub-code generator to create it automatically. The generator is given the available functions, arguments, data types, some details (in/out/inout, function IDs, etc). Once this is written (in a format called IDL), the complier produces client stubs, server stubs, and a shared header file.

RPC Procedure

A full RPC call is below:

- Client function calls client stub.

- Client stub marshals parameters, builds request message, calls OS.

- Client OS sends message to server OS.

- Server OS hands message to server loop.

- Server loop calls the relevant server stub.

- Server stub un-marshals parameters, calls the function.

- Function runs.

- Server stub marshals return value (and other data), calls server OS.

- Server OS sends message to client OS.

- Client OS hands message to client stub.

- Client stub un-marshals return value (and other data), returns to caller.

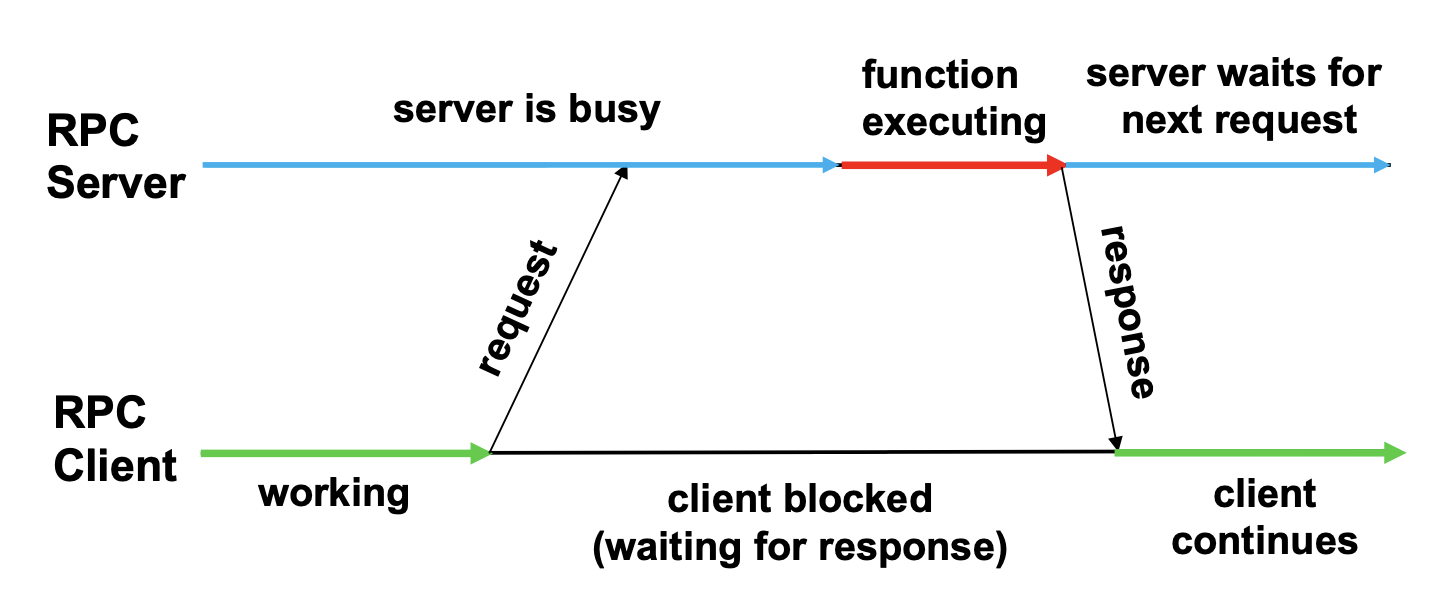

In the standard RPC, the client blocks during the RPC call, just like a normal function would. With asynchronous RPC, the client continues to run as soon as the server acknowledges the request, and there’s no direct return value; this prevents the client from waiting for the server and can be useful in cases where the client wants the server to do something without expecting a reply. It’s still possible to return a value with asynchronous RPC, however, if the server sends the return value back to the client via another asynchronous RPC.

Parameter Passing

Stubs copy data back and forth between client and server, and if our function uses call-by-value, this is straightforward. However, if it uses pointers—especially those pointing to complex data structures—things get more complex. The main problem is that pointers don’t work across machines, and we need to copy the data in memory that the pointer is referring to.

When passing a pointer as a parameter, there are three “modes” in which we use it:

- Input: we only use it as input and don’t modify it. Then, the client stub simply copies the value to the server, and the server stub discards the value after the call.

- Output: we only set the pointer’s value in the function, without looking at the original value. Then, the client stub ignores the value, and the server stub allocates space before the call and copies the value to the client after the call.

- Input-Output: we use both the pointer’s original value and also change it. Then, we copy the value in both directions.

The steps above assume that the data is easy to copy—that the data size is known. But what if we have a complex data structure like a tree with a bunch of pointers to nodes? Typically, we need some serialization of the data structure, but in general, this is very difficult and sometimes not supported.

Finally, there’s the issue of data representation: the client and server can have different endianness, data types, and machine types. To address this, we have a common representation “on the wire,” and each stub has code to convert from the local representation to the common one and back.

Binding

In the first place, a client needs to know where to send the request. We can either hardcode the IP and port (with a config file) or determine them at runtime; the latter is more flexible, allowing the client to use multiple available servers or adapt to server changes.

To look up the IP and port at runtime, we have a directory node for lookup. Both servers and clients know where the directory is, and the server registers themselves in the directory while the client looks them up when they need an RPC.

An example of binding in the DCE framework is below:

- Server starts, advertises itself in directory service with some descriptive name. Include IP, location, protocols, and interfaces—but not the local port number, since the server wants to be flexible to whichever port the OS gives it.

- Server machine runs a daemon called

dced, registers itself with it. - Clients look up server IP in directory, contacts

dcedon server machine for the server’s current endpoint port.

Failure Handling

RPCs can go wrong for many reasons due to the network and possible crashes on the client or server side.

If communication fails (can’t bind, can’t connect), the RPC throws an exception. If the client doesn’t receive a response, then either the request was lost, response was lost, or network delay is too high.

- To be robust to lost requests, we can simply retransmit until we get a response; this makes the remote function run “at least once.” If we want to avoid this function running duplicates, the server can associate sequence numbers to the requests and ignore duplicates, ensuring that the function runs “at most once.”

- For lost responses, the server can keep a cache of responses and retransmit the response (without re-running the function) whenever a duplicate request arrives.

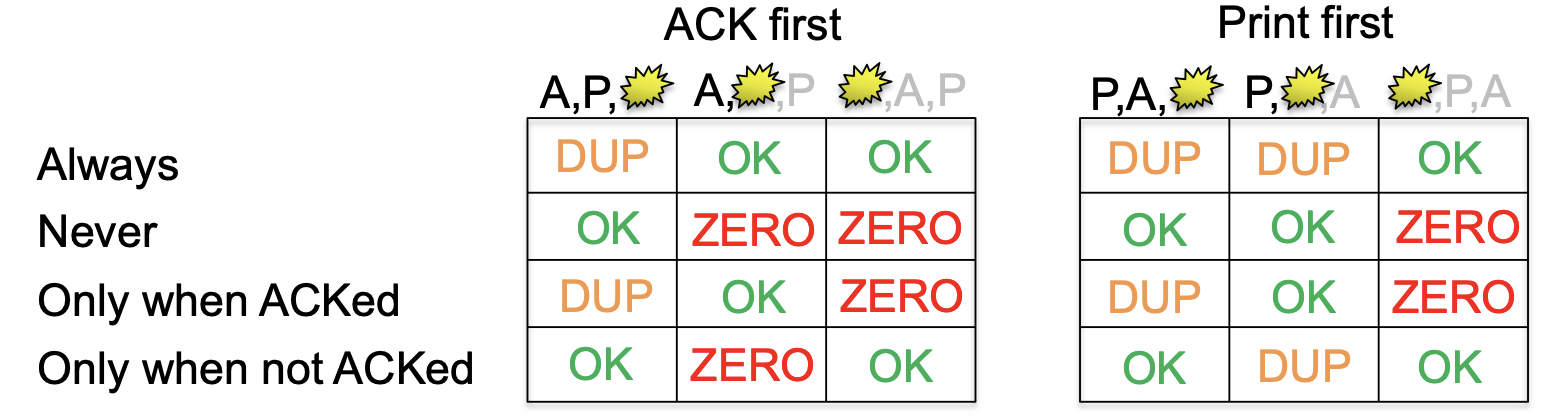

If the server crashes, it’s difficult to tell whether the function was executed or not. Even with the server contacting the client on reboot, it’s impossible to guarantee that the function executes exactly once. For example, in the scenario of printing, the following are outcomes depending on when the server crashes (after, between ACK and print, before) and how the client decides to retransmit (always, never, only on ACK, only without ACK):

If the client crashes after sending the request, the server may be doing work for nothing, and its response might cause confusion in case the client reboots and sends another RPC. There are three solutions:

- Extermination: client remembers each request via logging and kills pending requests after reboot.

- Reincarnation: client starts a new “epoch” after rebooting and tells all servers to kill requests from old epochs.

- Expiration: RPCs only run for up to

seconds and must ask permission to continue afterwards.