Virtual addresses are converted into physical addresses via a process-specific page table. Each entry in the table contains a virtual page number, a valid bit (whether the page is in physical memory), the physical page number if it’s available, two reference bits (recency, used for replacement), dirty bit (whether page was written to), and permissions.

If a location that’s not in physical memory is accessed, a page fault exception is raised. The kernel then handles page replacement before returning to the process.

However, we have a lot of virtual addresses, and storing this table naively takes up a bunch of space. There are two general methods to optimize space usage: multi-level page tables and inverted page tables.

Optimized Page Tables

Multi-Level Page Table

Multi-level page tables build a hierarchical tree to store entries. On a 64-bit address, the bottom 12 are used for page offset, and we split the upper 52 into 4 groups of 9 bits (ignoring the remainder). Each group is then one level in the tree, so the first group indexes into a pointer to the second level, the second level points to the third, and the third points to the fourth, which stores the entries.

Note that we use groups of 9 bits since each pointer is 8 bytes, so each level of the table perfectly fits in the size of a page.

Since most pages are usually unused, this tree has most pointers as NULL, thus saving the space of most unused entries. Also, memory access has spatial locality, so other memory accesses will usually be in nearby pages and thus the same nodes in the tree.

Inverted Page Table

Inverted page tables store one entry per physical page instead of virtual page (since there’s a lot less physical memory than virtual memory). The table is implemented as a chaining hash table; a process indexes into it by hashing the virtual page number and process id, and then it checks the chain for the corresponding entry.

Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

Though the methods above improve space usage, they significantly decrease access speed. To improve this, we can keep a special piece of hardware memory called the TLB that stores recent virtual-to-physical page translations. When a translation is needed, the MMU checks the TLB as well as the page table for the physical page.

We also need to make sure TLB entries are in sync with the page table.

- If a TLB page is updated, the page table needs to update its dirty bit.

- If a page is evicted from the page table, its entry must be removed from the TLB.

Moreover, the TLB must also be process-specific, so it either contains pid for each entry or clears its entries when switching processes.

Parallel TLB

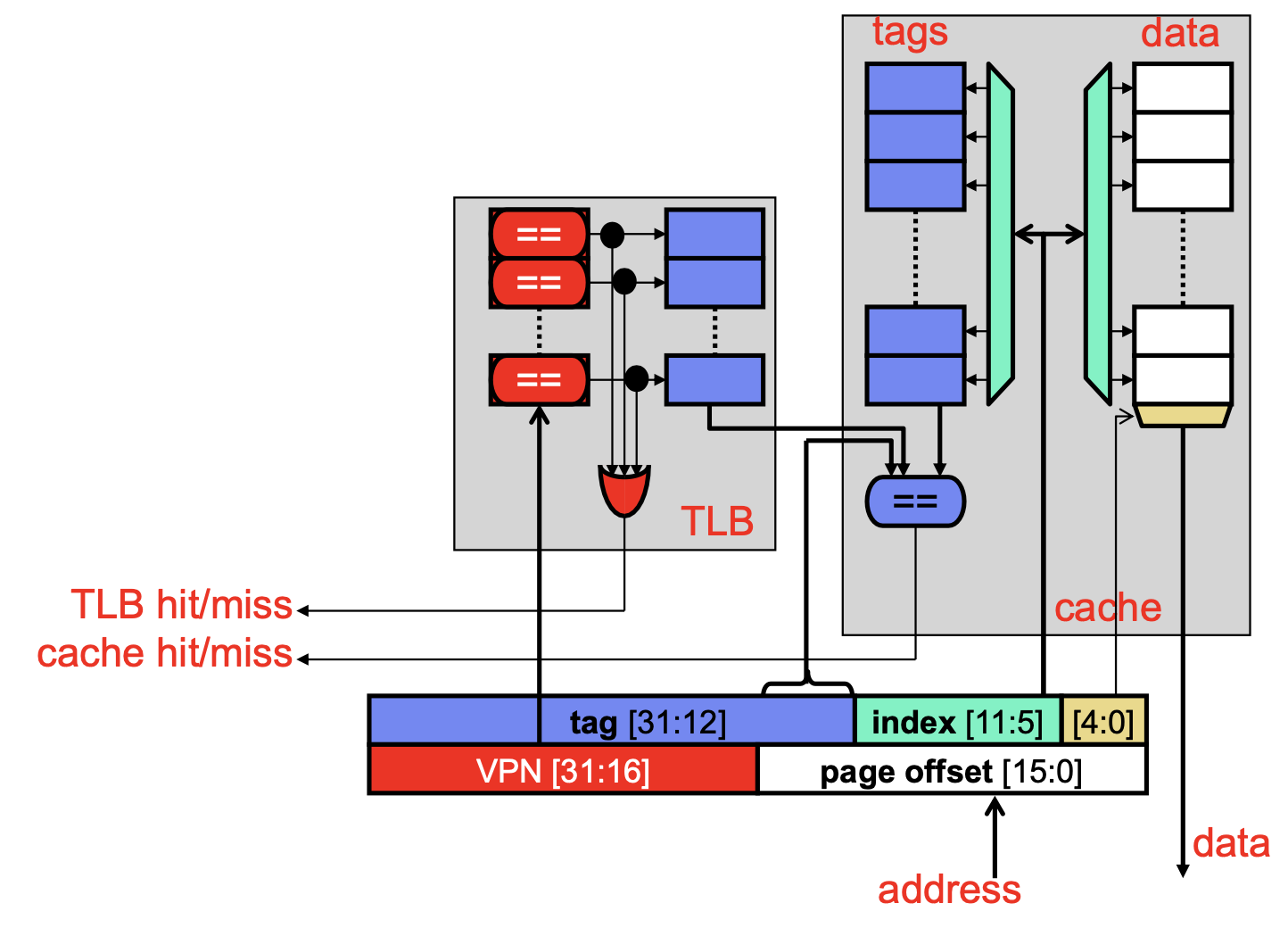

In a basic setup, the TLB must translate virtual addresses to physical addresses before we access whatever’s at the physical address. We can parallelize this, under certain conditions.

First, we observe that the page offset in the virtual address is the same as the page offset in the physical address; thus, we already know that part of the address after translation. If the index bits used by the physical cache are also within the page offset, then we already know the index of the cache to check before translation.

Thus, if the virtual page number and index bits don’t overlap (cache size / associativity ≤ page size), then we can access the cache in parallel with the TLB. We can use the translation to check the tag afterwards.