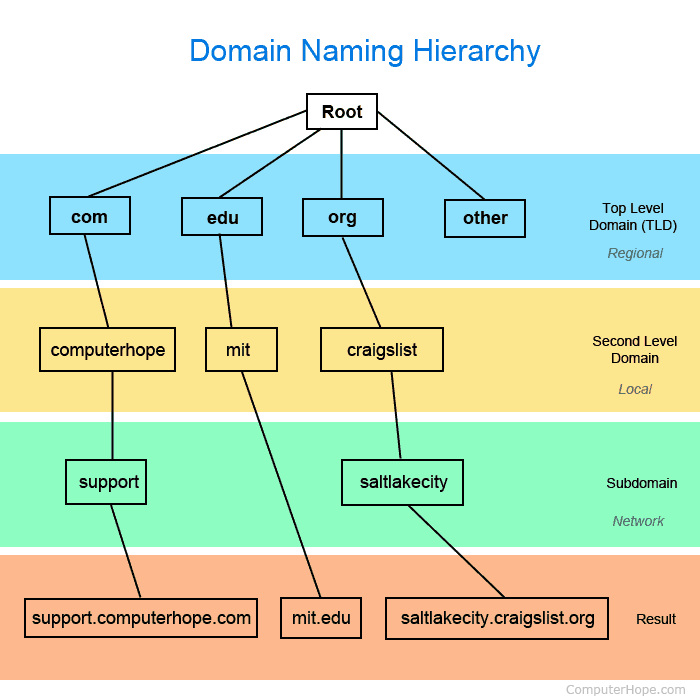

The DNS associates human-readable names to host IPs on the internet (along with some other information like CNAME and MX). It uses a hierarchical, structured namespace; the first level is managed by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), and authority over the other levels are delegated to registrars and organizations.

The namespace is divided into zones, each with an authoritative name server that knows, for each name in the zone, which machine corresponds to which name or which other name server is responsible. The top-level domains (TLDs) belong to the root zone with root servers, and the lower-levels are responsible for their own authoritative servers.

Historically, 13 root servers store entires for all TLDs, and DNS server are hard-coded to map to the root servers when starting a resolution. To protect against attacks, root server hardware is spread all over the world but share the same IP, and anycast routing sends each request to a nearby server.

Name Lookup

Starting with the root server, name lookup can be either iterative or recursive:

- Iterative: a local machine requests its local DNS server, and the local server asks the root server for the TLD resolution. The root server responds with the authoritative server for the next level, and the local server then asks that, and so on.

- Recursive: a local machine requests its local DNS server, and the local server asks the root server for the entire name’s resolution. The root server asks the authoritative server of the TLD, and the authoritative server asks the next authoritative server on the next level, and so on.

The iterative approach puts more load on the local server, and the recursive approach puts more load on the authoritative servers. Since we generally expect many more users, the iterative approach tends to balance out the load more.

To speed up lookups, servers commonly cache the results of past lookups. Both the local machine and local DNS server cache, and if our lookup is recursive, the other servers cache as well.

Local DNS Setup

In a typical setup, a network administrator:

- Configures a local DNS server with the address of at least one root server.

- Configures a DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol) server with the IP address of the local DNS server.

When a machine joins the network:

- It broadcasts a packet to find the local DHCP server.

- The DHCP server responds with an IP address for the machine and the IP address of the local DNS server.

- The machine then sends DNS requests to the local DNS server, which forwards them to the root servers.

Akamai Case Study

Commonly, DNS responses are always the same, regardless of who’s asking. However, this doesn’t need to be the case.

Akamai is a content delivery network (CDN) that makes websites faster by bringing the data closer to where its users are. Akamai has edge servers all over the world that store website content (like images); when a user access the website, their browsers get content from the nearest available edge server.

For example, if a user access cnn.com, which has an image stored by Akamai and saved on a7.g.akamai.net, then:

- The root name server is asked for the

.netserver. - The

.netname server returns domain delegation for.akamai.netto Akamai’s top-level DNS server. - The top-level DNS server then returns domain delegation for

.g.akamai.netto a low-level DNS server, which is selected based on proximity to the requesting client via geolocation—a mapping from IP addresses to physical locations. - The low-level DNS server returns IPs of servers available for the request, based on server health, load, and other factors.

DNSSEC

DNS is vulnerable to a variety of attacks. For example, the Kaminsky attack attempts to intercept authoritative DNS server responses with redirection to the adversary’s IP; this poisons the DNS server’s cache and results in future requests to each the adversary’s server, allowing it to control the entire zone.

The DNSSEC (DNS Security Extensions) protects DNS against spoofing and corruption using cryptography. On a high-level, each domain has a public-private key pair. It uses the private key to sign its DNS records, and resolvers use the public key to decrypt and validate its responses. The ensure the validity of a server’s public key, its parent also signs and publishes it in DS record; resolvers then use the parent’s DS record to validate the public key (starting with the root server, whose public key is well-known).