A distributed system at large scale must be able to handle problems smoothly. A fault occurs when some component of the system isn’t working correctly, which can be caused by an infinite number of physical, electrical, or software-related reasons. At scale, these faults are occurring all the time, and we cannot simply stop the system to deal with it.

There are three types of faults:

- Crash faults: node simply stops due to crash or power loss.

- Rational behavior: node’s owner manipulates it for some other motive.

- Byzantine faults: node has arbitrary or malicious behavior.

Moreover, faults may be correlated. For example, if an overloaded machine crashes, the load on other machines increase, potentially leading to more crashes.

To be robust against faults, we can build a service with 🖨️ Replication. Then, a client can send a request to each machine, the machines coordinate and return results, and the client chooses one of the results (like the most common one). The tricky problem here is that we need all machines to process the requests in the same way and same order; otherwise, their states will diverge. To do so, the machines implement a deterministic state machine—here, called state machine replication—and reach a consensus on the processing order.

Consensus

For consensus, each process can propose a value, and the processes agree on which value to use. Formally, the consensus solution must satisfy:

- Termination: every correct process eventually decides.

- Validity: if all processes propose the same value, then every correct process uses that value.

- Integrity: every correct process decides at most one value, and it can only use values that have been proposed.

- Agreement: if some correct process decides a value, then every other process must also decide that value.

Unfortunately, the FLIP impossibility result proves that no asynchronous algorithm can achieve consensus in the presence of crash faults. Thus, methods can only guarantee some of the properties above; 🏝️ Paxos is one such example (for crash faults).

Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT)

Byzantine faults are much more difficult to tolerate than crash faults since anything can happen. From here on, we assume that up to

Byzantine Generals

Consider the Byzantine Generals problem: we have

Each general can learn the opinions of other generals,

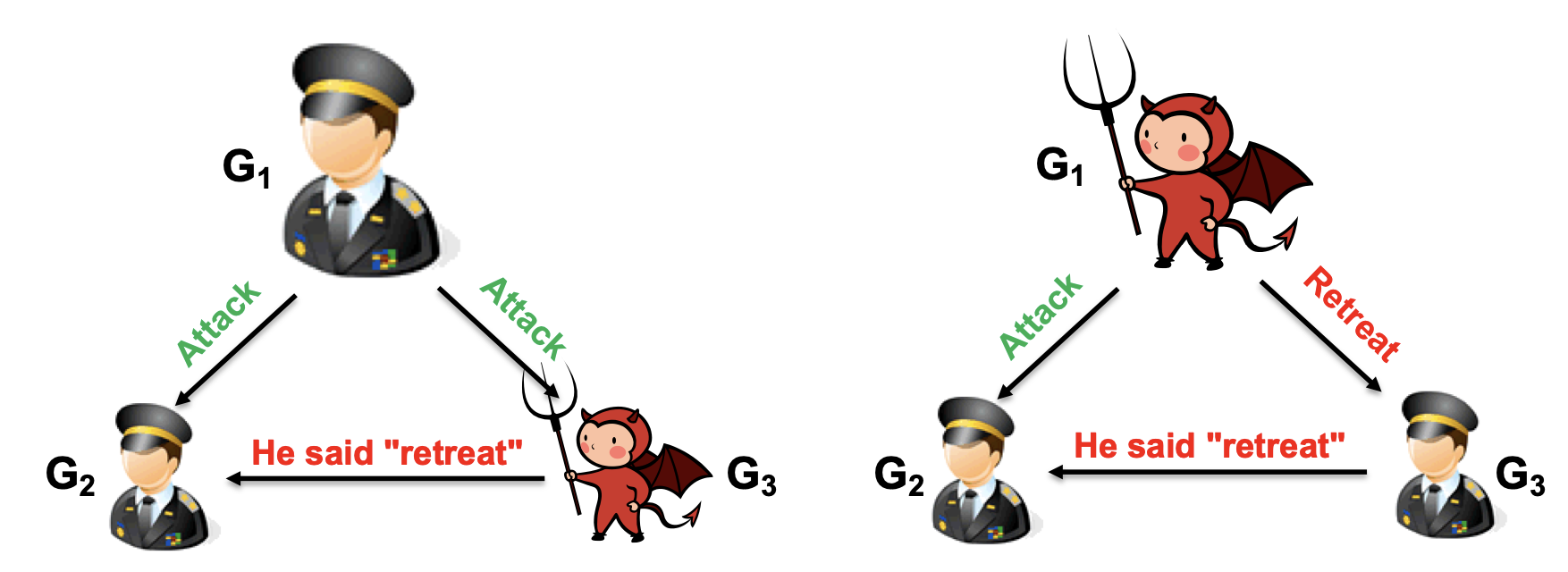

Let’s consider a single opinion; we’ll call the sender the commander, and the recipients are lieutenants. First, we can bound the maximum number of traitors. Consider

There is no way for

With

This will not work for

- If the commander is a traitor, there is at most one traitor among the lieutenants and thus reduces to the problem with

. - If the commander is loyal,

can produce a single discrepancy, but since there is at least one loyal lieutenant and commander, the majority will still be correct.

Byzantine Generals with Signatures

The traitors are a problem because they can change what the commander actually sent when forwarding it to other lieutenants. If we have each general sign their messages, however, then traitors cannot change it.

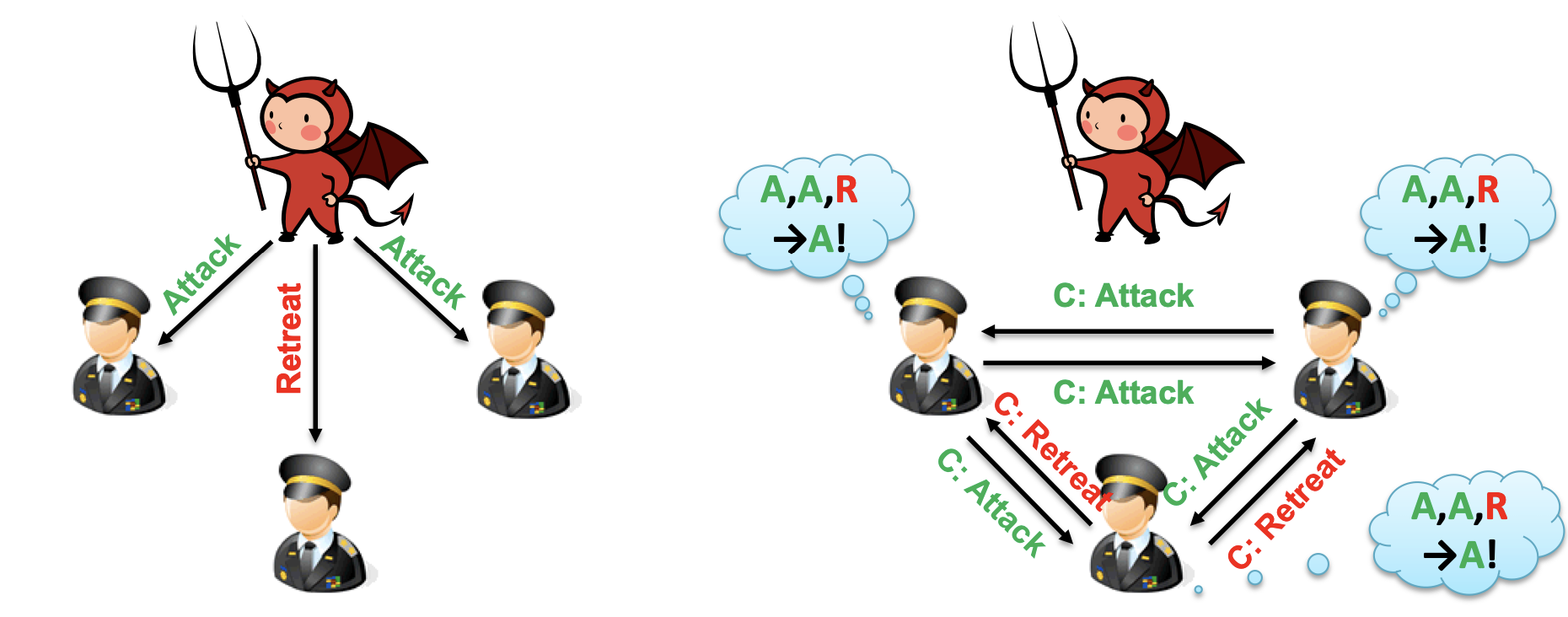

Now with

The only problem we have is that with multiple traitors, a traitor commander can send multiple signed values to the traitor lieutenants, which forwards them differently to the other lieutenants. To prevent this, we must ensure that if a signed order is received by a loyal lieutenant, it’s also received by all other loyal lieutenants. To do so, when a lieutenant receives a signed order:

- If they haven’t seen it before, they add it to their set of valid orders.

- If the order doesn’t have endorsements from

other lieutenants (sent by others), they add their endorsement and sends it to all other lieutenants.

At the end of forwarding, the lieutenants use a deterministic function to pick an order from the set of valid orders. The main idea is that if the commander is a traitor but there are

Application

With our solution to Byzantine generals, we can ensure consensus in the presence of Byzantine nodes: each node is a general, and the commands are proposals for state-machine replication. The client will send its request to each node, each node proposes some request as the next one to execute, and they use a Byzantine-tolerant protocol to agree on a request; then, they each execute the request and reply to the client, and the client uses the majority response.

PBFT

PBFT is the classical protocol for this procedure. It uses signatures (as discussed above), but the network is asynchronous—messages can be delayed. Because of this, there’s no way to tell whether a message has been sent is or taking a long time; thus, we need

At a high level, it proceeds as follows:

- Client sends request to primary node.

- Primary multicasts request to other replicas via a multi-round protocol.

- Replicas execute request and send responses to client.

- Client waits for

matching responses and uses it as the result.