Since dependent instructions introduce hazards in the 🚗 Datapath pipeline, we can improve throughput by scheduling independent instructions. This fills in the load-to-use delay slots in scalar pipelines and enables parallel independent instructions in superscalar.

Data Dependencies

Dependencies occur when we use the same registers, and there are multiple dependency types that limit throughput. Some are “true” dependencies that must be enforced, but others are “false” dependencies that are only dependencies because they use the same register, not because the data flows from one to another.

- RAW: read after write, a true dependence.

- WAW: write after write, a false dependence since we can just write to different registers.

- WAR: write after read, a false dependence again since we can just write to a different register.

Static Scheduling

Static scheduling is done by the compiler, which moves instructions to reduce stalls during compilation. To be effective, the compiler needs a large scheduling scope to find independent instructions.

However, there are some limitations to compiler scheduling:

- Instructions cannot be moved past branches.

- We need enough registers to hold additional “live” values. This is inherently limited by the 📋 ISA.

- Loads and stores might use the same memory location, so their ordering can’t change. Figuring out whether loads and stores reference the same location is called alias analysis.

- There’s no information about cache misses or other runtime event that can inform scheduling decisions.

SAXPY

SAXPY (Single-precision A X Plus Y) is a test case for scheduling that performs a linear algebra routine:

for (i = 0; i < N; i++) {

Z[i] = (A * X[i]) + Y[i];

}Static scheduling works well here since all loops iterations are independent. By unrolling the loop, we can interleave two iterations of the loop to reduce stalls.

Dynamic Scheduling

Dynamic scheduling is done in hardware in out-of-order processors. The general idea is that hardware re-orders instructions within a sliding window while keeping the illusion of in-order execution. This approach does loop unrolling transparently, and it can also unroll branches via 🕊️ Branch Prediction.

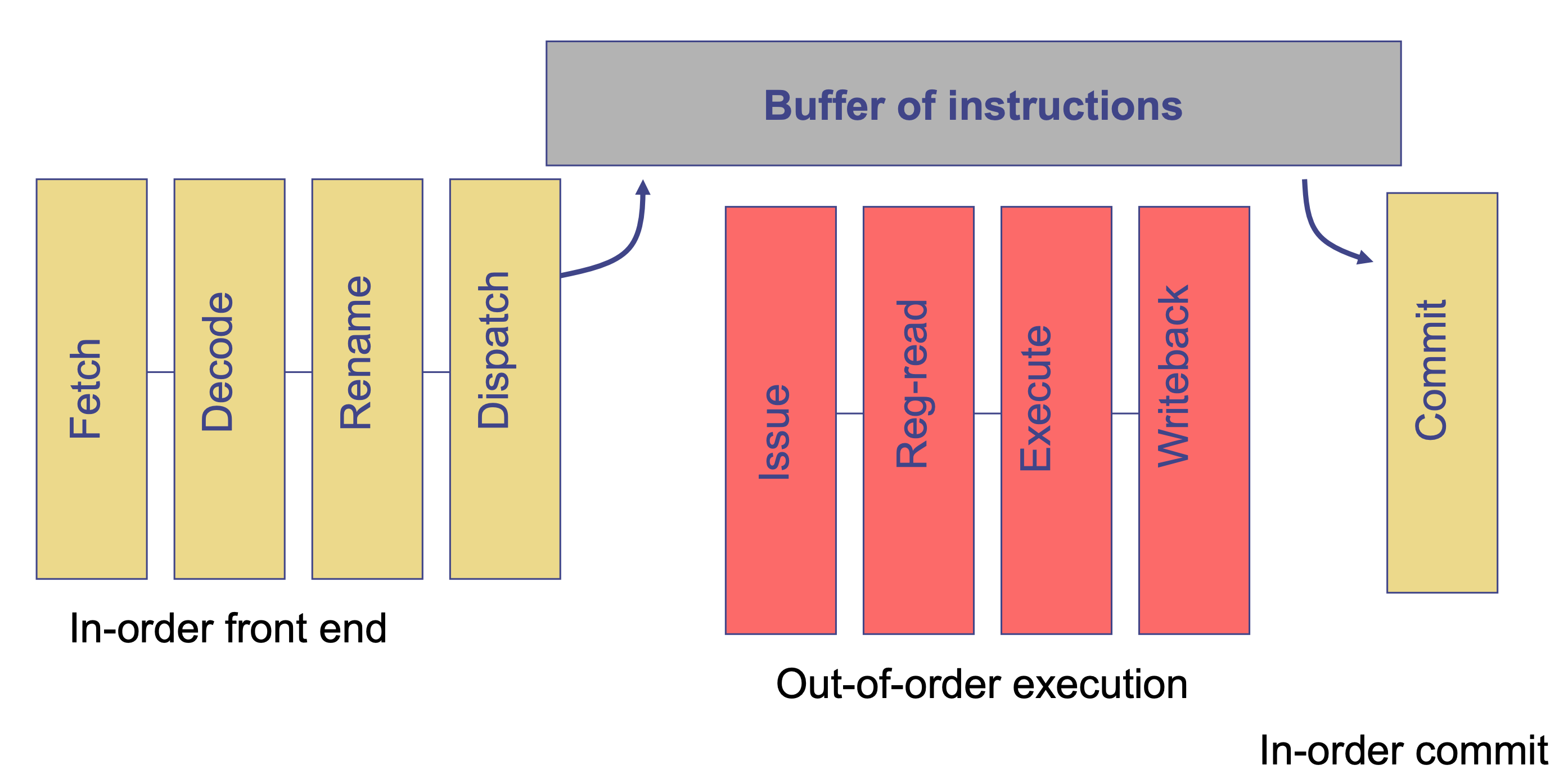

An out-of-order pipeline fetches and decodes instructions in order, runs them out of order, then commits in order:

This pipeline uses two ideas:

- Register renaming, which eliminates false dependencies.

- Dynamic scheduling, which enforces true dependencies while increasing throughput.

Register Renaming

The register renaming algorithm associates “architectural” registers—ones specified by the instruction—to physical registers. It maintains a mapping from architectural registers to physical registers in a map table as well as a list of free physical registers.

During decode, the instruction’s input registers are mapped to physical registers. Then, we use the free list to get a physical register, which we use as the instruction’s output; thus, we map the instruction’s output architectural register to the free physical register.

To free previously used registers, we also need to keep track, for each instruction, the old physical output register that the architectural output register maps to. Then, when this instruction is committed, we know that the the old physical output register is no longer needed—since commit happens in-order, all previous instructions that would’ve used the old physical register’s value have been completed, so that register is free to store new data.

Since we use a free output physical register for each instruction, we remove all false dependencies. Meanwhile, the mapping preserves true dependencies.

Reorder Buffer (ROB)

Renamed instructions and the old physical output registers are saved in the ROB, which tracks all in-flight instructions in-order (from fetch to commit). This is necessary to enforce in-order commit and ensure misprediction recovery and freeing physical registers.

During recovery, we need to remove the wrong instructions from IQ and ROB, restore the map table to before misprediction, and free destination registers. One way to restore the map table is log-based reverse renaming, which uses the old physical output registers we tracked to iteratively undo the map table and free list changes.

Dynamic Scheduling

Renamed instructions are also dispatched into an Issue Queue (IQ), which holds instructions that will be run. The IQ also tracks whether each physical register is “ready.” When an instruction is added to IQ, its output register is set as not ready.

At each cycle, if all input registers for an instruction are ready, that instruction is ready. We select the oldest ready instruction to run, and we set the output register of that instruction as ready. (Note that if the instruction takes multiple cycles, we set the output register later.) This procedure is called Select (get instructions to run) and Wakeup (ready next instructions to run).

Memory Operations

Memory operations are harder to deal with since unlike registers, the memory address is only known when it’s actually computed—it’s not known during rename. Thus, we can’t fix false dependencies with renaming.

Store Queue

Instead, we’ll have store instructions write to a FIFO Store Queue (IQ); the values in SQ are only actually stored (by sending to store cache) during commit. A load instruction will then check the SQ—called memory forwarding—along with the store cache; the load chooses the youngest SQ entry with the same address that’s older than itself.

However, it’s still possible for aliasing if a load that comes after a store searches the SQ before the store even adds an entry to it (RAW violation). There are two solutions:

- Conservative load scheduling: load waits until all older stores have executed.

- Optimistic load scheduling: run loads earlier with speculation.

Load Queue

Optimistic load scheduling uses a Load Queue (LQ) that tracks when loads run and detect load ordering violations. When a load executes, it records its address and age as well as the birthday of the entry received from SQ. Then, when a store executes, it checks LQ to see if there’s a load that should’ve seen the stored value.

If there was an incorrect load, we flag the violation and need to rollback the instructions.