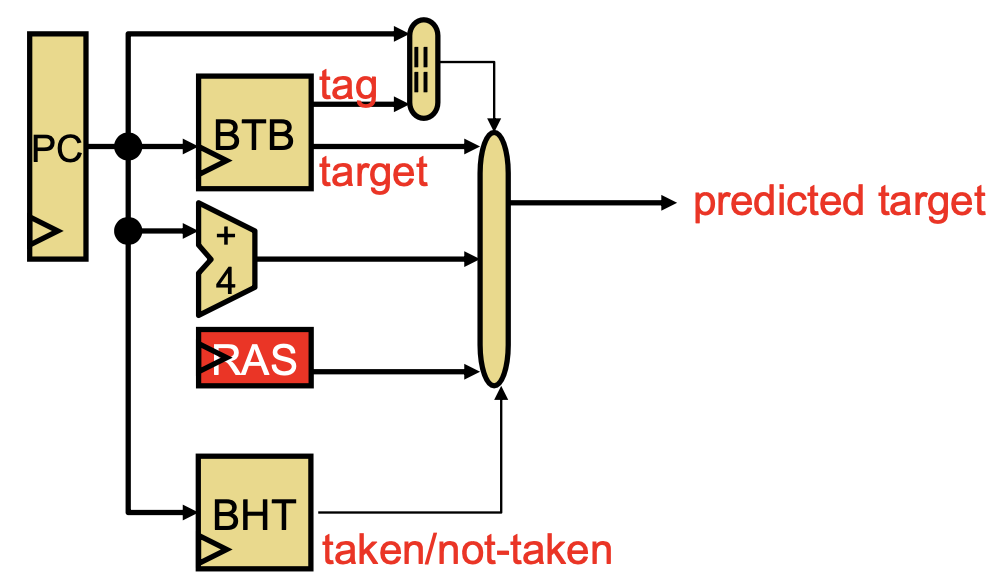

Branch prediction speculates on which control branch to take before the correct result is known. Naturally, this is done in the fetch stage, and it needs to answer three questions:

- Is the fetched instruction a branch?

- Should we take the branch or not?

- Where does the branch go?

Question 1 and 3 are easily answered during the decode stage; however, this would require the processor to wait one cycle for every instruction before fetching the next one. Thus, we have to do it during fetch, in parallel with fetching the instruction from memory—this means that the only information we can use is the PC.

We use the key idea behind dynamic branch prediction: to “learn” from the past to predict the future. Note that “learning” isn’t anything fancy—generally, it’s some form of recording the past.

We need multiple components remembering different things, and we’ll cover them one-by-one below.

Branch Target Buffer (BTB)

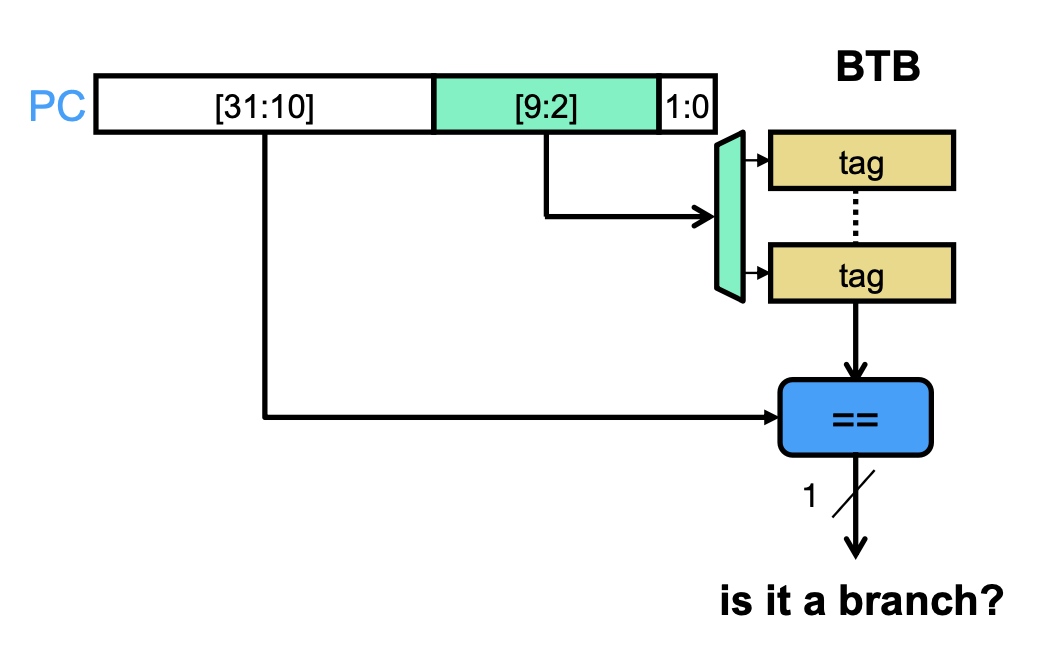

The BTB records a list of past branches we have seen. It maps the PC (specifically, bits 9 to 2) to a 1-bit value denoting whether there’s a branch at this PC or not. Note that we don’t use the entire PC to save space; however, it’s possible for two PC’s to have the same 9:2 bits and access the same entry—called aliasing—leading to misprediction.

We can improve this design by noting that we can only record actually-taken branches (filtering out branches that are never taken). Moreover, our entry can contain the remaining 31:10 bits—called a tag—in the PC to avoid aliasing. Thus, our improved BTB maps the 9:2 bits to a tag; we set the tag if the branch is taken, and we perform prediction by matching the recorded tag with the current 31:10 bits. If it’s equal, we move on to direction prediction; otherwise, we assume that the branch isn’t taken.

Branch History Table (BHT)

Just because a tag is set in the BTB doesn’t mean it’s always taken. We need a direction predictor to track whether it’s taken or not taken (T/N).

Bimodal Predictor

The bimodal predictor, much like the BTB, maps the 9:2 bits of PC to 1 bit in BHT indicating T/N the last time this branch was run. This means our branch will go the same way it did last time.

Two-bit Saturating Counters

One problem with the bimodal predictor is that it “changes its mind too quickly.” We can replace the 1-bit T/N with 2-bit N/n/t/T. Now, if we’re in T or N, it takes two mispredictions to “change its mind.”

Correlated Predictor

We also observe that branch outcomes are correlated (for example, multiple if statements with same condition). To incorporate history, we keep the recent branch outcomes in the Branch History Register (BHR) and use the PC XOR with BHR to index into BHT.

Hybrid Predictor

However, using PC XOR BHR to index BHT requires a lot of capacity. We can combine the bimodal predictor for history-independent branches with the correlated predictor for history-dependent branches. Specifically, we’ll have a chooser that selects which predictor to use.

Branch Target Predictor with BTB

Finally, we need to know where the branch goes if it’s taken. We can track this information in the BTB along with the tag; thus, the PC’s 9:2 bits map to the tag and the target address used the last time a branch was taken at this PC.

Note that this works because most control instructions are direct targets—targets encoded in the instruction and constant every time it’s used. For indirect targets that rely on a register, we need more hardware. Luckily, this is uncommon in most scenarios—the main common case where this happens is function returns.

Return Address Stack (RAS)

Thus, we can keep a RAS that keeps the PC location of function calls; when we return, we pop the top of the stack. We also need to track whether an instruction is a call or return in another table or in the BTB.